Every stargazer has a “first telescope” story. Here’s mine.

Like many backyard astronomers, one question I get asked all the time is “When did you get interested in the stars?” The truth is, I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t drawn to the night sky. Maybe part of the reason was that my family lived on an orchard under a splendid, dark rural sky. For me, the stars were as much a part of nature as the birds in the trees and the bugs crawling on the ground.

Unlike most of my astronomy friends, I never had a big “Aha!” moment when I found myself suddenly fascinated with the wonders of the universe. That’s not to say there weren’t some important episodes that remain fresh in memory many decades later — there were plenty. And one memory that stands out with crystalline clarity, even now, is my very first look at the Moon through my first telescope.

The year was 1971. I’d saved every penny from allowances, my birthday, and Christmas, and eventually amassed the astonishing sum of $100. That was a lot of money for a kid in the early ‘70s. I knew I wanted a telescope more than anything else in the world, and I was pretty sure that $100 was enough to make this wish come true.

That autumn, my family made its annual trek from our little hometown to the Big Smoke (Vancouver) to visit relatives. More importantly, I was finally going to have the chance to spend my $100 on a telescope. The day after we arrived, dad and I went downtown to go telescope shopping. We didn’t have much time, but I was sure that in a city as big as Vancouver, there’d be telescopes all over the place. There weren’t. After some unproductive searching, we eventually spotted a beautiful refractor in the window of a camera store. I nearly tore dad’s arm off hurrying him to the entrance, only to be greeted with a sign that read “back after lunch.” What?!? How could anyone think of eating at time like this? Had the whole world gone mad? “Don’t worry,” dad said. “We’ll go to the Bay — they have everything!”

Unfortunately, as great as the Hudson Bay Company department store was in the early ‘70s, “everything” didn’t include dreams — especially the optical kind with white, enamelled tubes on metal tripods. The kindly clerk talking to my dad did offer that they could order a telescope in and have it shipped to us. He flipped open a catalogue and pointed to a pair of curious looking instruments. “These,” he said, “are reflectors — they’re meant for astronomy.” That was good enough for my dad. And the fact that one of them was $100 meant it was also good enough for me. With that, our quest was over.

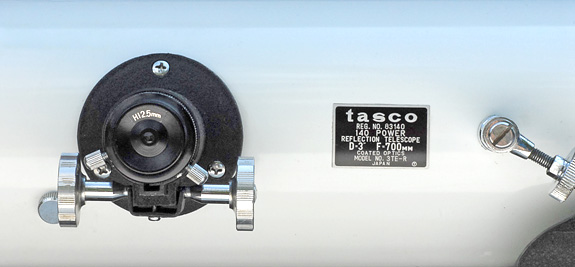

We had chosen a 3-inch Tasco reflector, a model named, appropriately enough, Luna. It claimed a magnification of 140×, which was surprisingly modest for a beginner’s telescope — even back then entry level scopes were marketed on the basis of magnifying power. Luna came with three eyepieces (23mm, 12.5mm, and 5mm — all Huygenian design), a nifty zoom Barlow, and an impressive-looking altazimuth mount. Of course, I didn’t know what any of that really meant and, in my excitement, much less did I care. I had bought a telescope — my telescope!

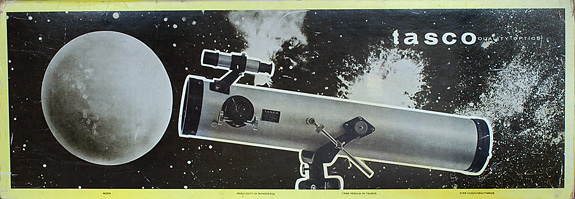

I can’t say how long it really took for my telescope to arrive. It might have been only a couple of weeks, but to an eager kid awaiting nothing less than the fulfillment of his greatest wish, it seemed to take months. Eventually the Big Day finally arrived. I came home from school and saw a large box wrapped in brown paper. I knew right away what it was. In milliseconds I had the wrapper off and was staring at a bright yellow box decorated with a portrait of the scope and amazing photos of the exotic deep-sky treasures I was sure I’d be seeing soon. But, alas, it turns out not all dreams come true — at least, not the way we imagine they will.

To say that my first night with a telescope was a disappointment would be to indulge in an understatement so vast that it couldn’t possibly exist in a finite universe. Dad and I got the scope assembled okay, but once outdoors, we couldn’t see a thing. Matters weren’t helped by dad’s instance that we try using it without eyepieces first — to avoid unnecessarily complicating things. Of course, all we saw when we looked in the focuser was the silhouette of the secondary mirror, or as dad called it in tones of increasing frustration, “that damn bull’s-eye thing.” Dad didn’t know much about telescopes. I knew even less.

On subsequent nights I tried in vain to coax some tiny particle of wonder from my telescope. It was not to be. Even using eyepieces didn’t materially improve the situation. Sure, occasionally I’d chance upon a random star, but there was little to suggest that I’d be rewarded with anything approaching the splendors shown on the telescope’s cardboard box any time soon. Eventually, discouragement won out over youthful enthusiasm and Luna was retired to a quiet corner of my room. Once the object of my greatest excitement, it had become the source of my biggest disappointment. And that’s where the story would have ended, had it not been for my Uncle Bob.

Uncle Bob and Aunt Mary were our favourite relatives. Bob and Mary would make the trek from Vancouver to our orchard two or three times a year, occasions anticipated with much excitement. Maybe it was because Mary and Bob had no children of their own, but they were always very generous with me and my siblings. Bob could always make me laugh too. He had a tremendous sense of humour and was always ready with a joke.

Not only was Bob a natural born comedian, he was also a natural born tinkerer with a knack for being able to fix esoteric farm equipment — a trait my dad put to good use many times. Soon after they arrived for their summer visit, Bob noticed my telescope. Immediately, his eyes lit up. “I hear your scope isn’t working so well,” he said. “After dinner, let’s take it outside and see what we can figure out.”

That evening, Bob and I went into the backyard and set the scope down on the lawn. Looking up, we saw a fat crescent Moon gleaming in the deep blue twilight. Bob flipped through the manual and then spent a moment or two making adjustments to the telescope, looking first through the finderscope, then the eyepiece, back and forth a few times. Finally he turned to me. “Hmmm…” he said ambiguously, “try it now.”

I looked. And looked. And looked. And then I gasped. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. There in my telescope was the Moon — the actual Moon. It was the most real thing I’d ever seen. And it was beautiful. There were craters just like in the pictures, but even more surprising to me was the particular and peculiar greyness of the lunar surface contrasted with the dark blue sky. I’d never seen the Moon in colour before and the view was stunningly unlike anything I’d expected.

Looking in the eyepiece that summer evening I was suddenly connected directly to the universe beyond our orchard. My little reflector (with Bob’s help) had redeemed itself entirely. I was happy in that way only a child can experience — washed over by a wave of pure, incandescent joy. There could be no going back.

I still have the telescope. I’m thankful for that. Any time I want, I can relive childhood triumphs, but mostly it’s nice to have an old friend to casually poke around the sky with. I can also assess the scope’s performance without relying on memories tinted with the golden patina of nostalgia. And you know what? Luna is actually a pretty good scope.

The 3-inch f/9 primary mirror is a sphere, but a very good one. I’ve had it up on the test stand several times and have always been impressed by how smooth and zone-free it is. And as most telescope nuts know, a mirror of that aperture and f/ratio doesn’t need to be a paraboloid to deliver good views. As an experienced telescope user, I can also appreciate the scope’s mechanical aspects. Keep in mind, Luna comes from an era when metal was king. As a result, there’s very little plastic to be found. The mount is reasonably stable and the fine-motion altitude adjustment works nicely. The focuser, though of the .965-inch barrel size favoured by Japanese manufacturers, is one of the nicest I’ve used. It’s smooth, precise, and solid.

Of course, the real Achilles heel of so many beginner’s telescopes was (and often still is) the eyepieces and finderscope. My scope’s finder is miserable and, in hindsight, was the main reason my early experiences were so unrewarding. And, yes, the included Huygenian eyepieces are wretched by today’s standards. Really, only the 23mm is usable. Over the years, I’ve amassed a small collection of decent .965 eyepieces (mostly Kellners, but a few orthoscopics too) that greatly improve the view. But the scope really came into its own only a few years ago when my friend and S&T colleague, Dennis di Cicco machined an adapter so that I could use standard 1¼ eyepieces. Now the scope really sings.

With good eyepieces this little old scope shows as much as its 3-inch mirror is capable of — which is quite a bit. I can see Jupiter’s major belts and biggest moons, Saturn’s rings, all the Messier objects, and a wonderful assortment of double stars. And once in a while, I’ll dig out that 23mm Huygenian eyepiece for a look at the Moon and let myself be transported back to a time when summers were warmer, fruit was sweeter, music was better, and the universe was so very much smaller.

This view of the Moon was recently captured with my 3-inch Luna. The photo only hints at the amount of detail visible in this telescope on a good night.

Did you find this article interesting or helpful? If so, consider using this link the next time you shop at Amazon.com. Better yet, bookmark it for future use. Thanks to Amazon’s associates program, doing so costs you nothing yet helps keep this site up and running. Thanks!